Tent City for the homeless rises in John Prince Park

Palm Beach Post, by Joe Capozzi. February 4, 2020.

About 70 tents fill a stretch of John Prince Park off of Sixth Avenue South west of Lake Worth Beach.

The first time April Hill heard about “Tent City,” she’d just arrived at the West Palm Beach Greyhound station in December. She was more than 7 months pregnant, on the run from problems in Michigan and in search of warmer streets for the winter.

Nestled among the slash pine in a scenic public park west of Lake Worth Beach, Tent City, as it’s called by people who live there, might be Palm Beach County’s fastest-growing community.

But you won’t find it in any real estate listings. Word of mouth, on the streets and in social media, has worked just fine since it started going up last fall.

“As soon as we got off the bus, somebody asked me for a cigarette,” said Hill’s husband, Mike Irwin. “I told him we were homeless and he said there’s a place homeless people can stay.”

They hiked south 9 miles, Irwin lugging a stuffed duffle bag, Hill cradling her belly, until they saw a colorful patchwork of canvas and tarps through the brush along busy Sixth Avenue South.

There might have been 50 tents when Hill and Irwin pitched theirs under a shady banyan tree on Dec. 20, just in time for Christmas. Now there are at least 70 — lean-tos, makeshift shelters and tents of different sizes — spreading out from a restroom building at what was once a popular picnic pavilion.

The encampment, meandering along a patch of lawn nearly the length of a football field, is home to about 150 people, many from outside Florida, just about all of them struggling to repair lives disrupted by addiction, unemployment, family strife or mental illness.

It’s just a small, local piece of a larger national problem that’s far worse in places like California, the state with the highest unsheltered homeless population.

Florida, which ranks second, has had tent encampments, too, in places like Jacksonville, St. Petersburg and Fort Lauderdale.

But the Tent City that took root in September at the Commodore Pavilion in John Prince Memorial Park is the first of its kind in Palm Beach County, which is most known for ritzy Palm Beach and President Donald Trump’s winter White House.

“This is probably the most serious I have seen it during my career,” said Eric Call, who started working for the county parks department in 1984 and became its director in 2010.

“We haven’t had to deal with it at this level before. They’re coming from as far away as Kentucky. They hear through social media that you can camp here,” he said.

Some of the homeless have told county staff they are being dropped off by other South Florida municipalities looking to clear their streets of homeless people.

About 50 yards from the mulch-covered heart trail popular with morning joggers, a shiny blue park sign at the entrance to Tent City lists a phone number to call to reserve the pavilion — something that hasn’t been possible or even enticing because of the homeless invasion.

“It has in essence taken that whole picnic area out of our park system. We can’t rent it out,” Call said.

Because of its setting west of Interstate 95 near a city that has battled poverty and crime, the 700-acre park has been ground zero for the county’s homeless. Four years ago, the county started issuing permits to faith-based groups to use the Commodore Pavilion to serve hot meals for the homeless.

But the rise of the Tent City over the past five months, near an area in the park recently considered for a Major League Baseball spring training complex, represents the biggest test of patience and tolerance yet for park-goers and nearby homeowners.

It is forcing them to weigh their personal concerns for the less fortunate against disruptions to their own quality of life.

“Why is this being accepted? Who decided that my neighborhood should be a homeless shelter?” asked Carol Robbins-Garrett, who said she has seen homeless people lying across the park’s lake-fronting walking path and rifling through mailboxes in her nearby neighborhood.

Sheriff’s deputies can’t just kick them out, even though the park closes to the public at night, or even bulldoze the place.

The U.S. Supreme Court recognizes the rights of the homeless to use public spaces for life-sustaining activities such as sleeping and bathing if local governments don’t have enough shelter beds.

And Palm Beach County doesn’t.

The county adopted a 10-year plan to end homelessness in 2008. Today, there are 358 temporary emergency beds. But those beds are either full or restricted to people who must meet strict rules. The maximum stay is 90 days.

In 2012, the county opened the Senator Philip D. Lewis Center on 45th Street in West Palm Beach, where it contracts with four nonprofits that provide temporary housing.

But the center’s 60 beds are full, and there’s a 130-person waiting list. County officials are trying to open a second homeless resource center with 74 beds on Lake Worth Road a mile or so north of the park, but that won’t happen until 2022.

That leaves public parks like John Prince Park as a lodging of last resort for many of the county’s homeless population, estimated to be at least 1,400, including about 900 who are unsheltered, according to the annual 2019 Point in Time count. (Homeless advocates say the actual number is probably much higher.)

For many of those people, the park’s picnic pavilions, sports fields and shade trees are far more enticing places to sleep than under road overpasses, in Walmart parking lots or in the woods.

While not officially endorsing Tent City as an option, county staff hope that having one main area for the homeless will at least reduce the complaints in other parts of the park.

“It is a very delicate situation,” said Wendy Tippett, director of the county’s Human and Veterans Services department.

“We understand the homeless have immediate needs, but we also respect the rights of the park users, especially the local area residents who have the desire and the need to feel safe and feel like their park is a healthy environment to be able to bring their families to.”

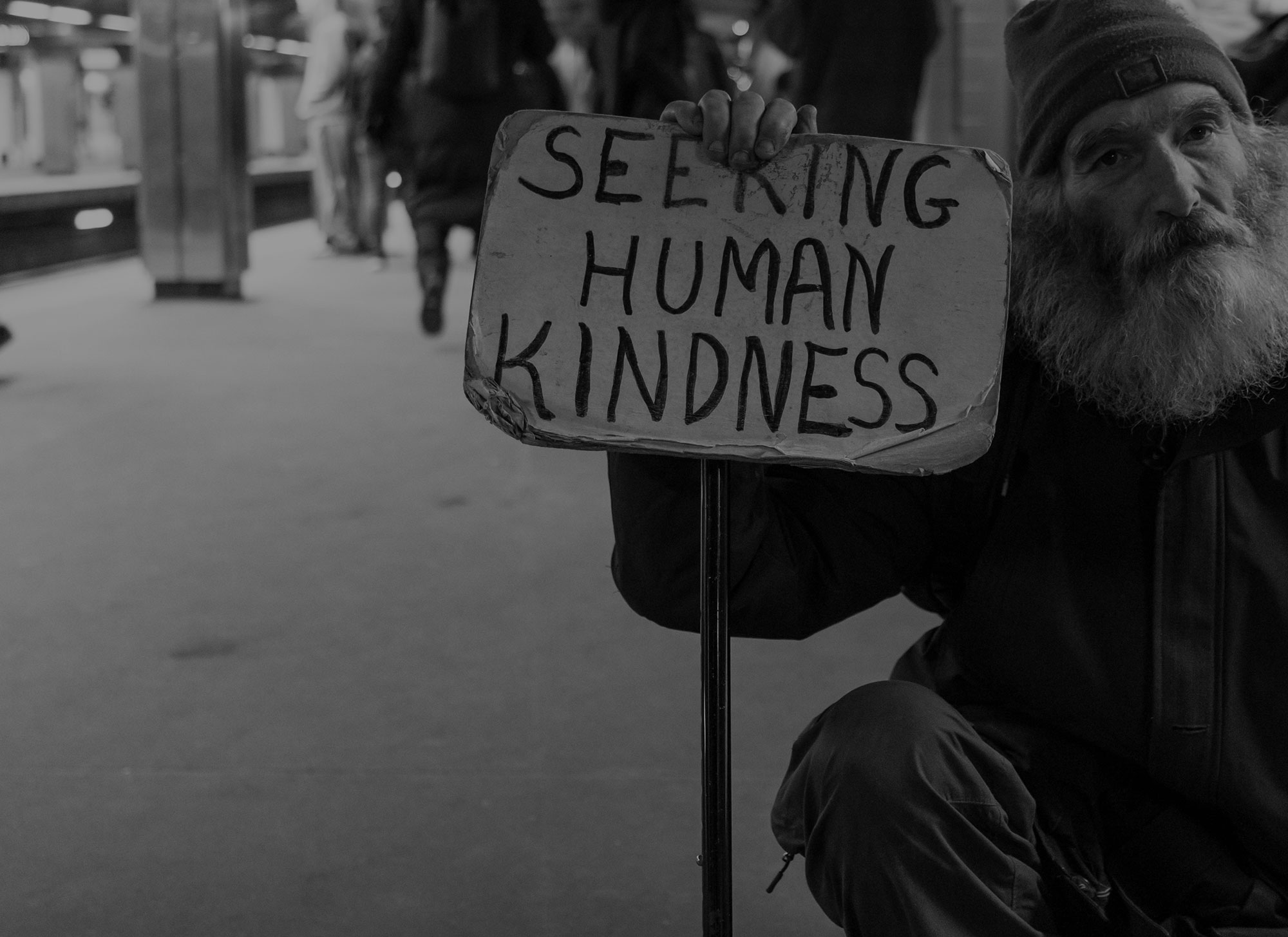

Some park users might consider Tent City an eyesore, but advocates for the homeless see it as a symbol of the county’s failure to adequately address a problem that has been in plain sight of government leaders for years but has now gotten out of control.

“To let it go this far is shameful. … I am ashamed of my county,” Shelley Vana, a former county commissioner who represented the district that includes the park, wrote Jan. 25 in a Facebook post with photos of Tent City.

Just a few hundred yards north of Tent City, on the other side of Sixth Avenue South, is a 4.3-acre dog park that opened in 2017. The county spent $2 million on “Lake Woof Dog Park” and its five fenced pens for large, medium and small dogs, each with gazebos, benches, drinking fountains and dog wash stations.

“They treat dogs better than they do their own fellow human beings,” said Sister Jean Peter Wilders, founder of The Servants of the Great I AM, a provider of hot meals and other support for the homeless since the 1980s.

Nodding toward the 50 people lining up at the Tent City pavilion for a dinner of ham, corn and noodles the other day, she added, “If I wasn’t such a devout Christian, I’d be tempted to give each of them a puppy and tell them to hang out in that dog park.”

Complaints about homeless people taking over the park started long before the rise of Tent City.

“This park has become unsafe and not family oriented,” according to a Tripadvisor review posted in September 2018 under the headline “Too many homeless living in the park.” The reviewer mentioned needles in restrooms, “clothing hanging from the stalls” and panhandlers approaching children.

Over the next year, complaints by local residents grew louder: Homeless men taking showers in a playground splash station, communal bars of soap left on water fountains, people sleeping in cars along Lake Osborne Road just outside the park.

Last summer, a local television news crew recorded images of an inebriated woman urinating at the shoreline of Lake Osborne.

“This used to be such a beautiful area. Now I’m afraid to go down there,” said Darrell Ramey, 64, who said he started carrying pepper spray after being “stalked” by a homeless person while walking his dog around the lake.

Brett Horowitz said he was walking through the park one day in January when he saw a disheveled man sprawled across the path. Concerned the man might be in need of medical attention, Horowitz pulled out his cellphone and called for help.

Suddenly, he said, the man sat up and started yelling. ”‘Why are you calling the police on me?’ He was inebriated. He threatened to kill me. Then he started following me,” Horowitz said.

He said deputies did not file a report and the man was taken away in an ambulance.

“My heart goes out to them,” Ramey said of the homeless, “but it seems like there’s no policing of their actions.”

Even the county’s parks staff has been harassed.

When a maintenance worker tried to clean the restrooms one morning at the Tent City pavilion, a homeless person sitting on the walkway and blocking the entrance demanded money — “a toll” — before moving, said Call.

At least one homeless person has wandered to the parking lot of the parks administration building, half a mile from Tent City, to panhandle.

Call issued a memo to parks employees last month with guidelines for dealing with homeless people in the park. And he has told county leaders about concerns raised by park users and residents in neighborhoods around the park.

“People are beginning to really be scared by the homeless behavior,” Call wrote Jan. 8 to County Mayor Dave Kerner, whose district includes the park.

Call agreed with a suggestion by Horowitz of “adding law enforcement resources around the clock.”

That idea is being embraced by some unlikely allies — a few of the homeless people living in Tent City, who told The Palm Beach Post that some tent dwellers are there just to do drugs while others have beaten, stabbed and robbed other tent dwellers at night.

Many attacks are not reported to law enforcement or park rangers, according to people in Tent City.

“I’m grateful we’re allowed to stay here, but it’s dangerous,” said Jamie Maxwell of Tennessee, who said her friend, Eric Walton, spent five days at JFK Medical Center in January after he was attacked inside his tent in the middle of the night.

Roger Rodriguez, an unemployed jewelry maker from Hollywood, shares a tent with a black pitbull puppy named Blondi, his bodyguard in a place he refers to as “Clown City.”

“It doesn’t feel safe,” said Rodriguez, 50, who lost his apartment after his wife died of an overdose. “A lot of people are on drugs. It’s very cutthroat.”

Rodriguez, 50, said he understands the county is trying to stem the spread of the homeless population throughout the park. But, he added, “If you’re going to keep us in one place, at least give us some security.

“It’s like they’re trying to get the riff-raff off the street and congregate us all in one spot. That just emboldens others to beat people up in the middle of the night while they’re trying to sleep.”

Now, Rodriguez said he and his neighbors in Tent City try to keep an eye on each other.

“I feel like we’ve been abandoned, really,” he said. “It’s like we’re invisible.”

The Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office used to have a dedicated parks patrol unit, but that was discontinued in 2010 because of budget cuts.

Deputies still patrol the park and take action as needed, but “arresting people is not the long-term solution when in fact no crimes have been committed,” PBSO spokeswoman Teri Barbera said in an email.

In an interview, Kerner, a former police officer, said he is working with Sheriff Ric Bradshaw and County Administrator Verdenia Baker on solutions. He said one idea is to put the unarmed park rangers under PBSO.

“I pass it every day on Sixth Avenue on my way to the county (administration) building. I’m not happy about it,” said Kerner, whose district includes the park.

“It’s not the policy of the Board of County Commissioners to corral the homeless population into a county park. That concept can’t remain in place. While this issue predates me, it certainly is going to be resolved in the near future.”

Advocates for the homeless aren’t optimistic.

The sisters with The Servants of the Great I AM said they have fought county resistance to their efforts to help street people living in the park for years.

“All of sudden they’ve allowed these tents with absolutely no plan in place. Now, we have upwards of about 70-plus tents and 150 people with one bathroom,” said Sister Chris Daniel.

“I understand the park is for families. We get that. But we have been battling with the county for years for housing. And Palm Beach County is one of the richest counties in Florida.”

In late 2018, Fort Lauderdale officials cleared out a downtown tent camp of 75 homeless people with help from a $4 million program that relocated them into temporary housing. Months later, though, other small encampments started popping up in other parts of the city, according to news reports.

In 2015, West Palm Beach had a small tent encampment around its shuttered City Hall building that grew out of the Occupy political movement. The tents were legally cleared away after the site was sold to a developer.

But the homeless didn’t go far. Last year, the city blasted a loop of the children’s songs “Raining Tacos” and “Baby Shark” in a controversial effort to run off homeless people who were lying about on the patio of the nearby Lake Pavilion.

County officials haven’t done anything like that at John Prince Park.

In fact, many homeless and their advocates offered praise for compassionate park rangers, some of whom they know on a first-name basis. And they said they appreciate the county’s Parks to Work program and Homeless Outreach Team of social workers that offers help and advice.

In November, commissioners agreed to hire three peer counselors to work with “HOT Team” social workers. But advocates wish the county could do more.

“Give me a place. Give me a building. Lord, just a place. If we can let them feel normal, then we can give them a chance to climb out,” Wilders said.

“All we are asking is that they’re treated like human beings. ‘They’re nothing but bums’ — that’s what people say. But that’s not true. You should hear their stories.”

Hill, the pregnant woman, said her parents, drug addicts who died last year, used to sell her for sex when she was 12 and 13 to drug dealers in exchange for crack cocaine.

Irwin, who said he grew up in foster homes, said he was 6 when his abusive mother traded him to his grandmother for a car — “a Thunderbird, cherry red.”

They came to Tent City after Hill got arrested on shoplifting and drug charges earlier this year in Michigan and Tennessee. “I stole so I could eat,” said Hill, who was arrested for shoplifting at a Home Depot in Wellington in 2012.

“It’s hard living like this,” said Hill, 31. “I cry every day.”

Elizabeth Casal of West Palm Beach moved into Tent City on Jan. 23. She said she had been sharing an apartment until a year ago when she left because of her roommate’s drug habit.

“I’m trying to get into the Lewis Center but it’s taking so long,” she said.

Michael Foley, 55, said he worked as a technician for the county’s Engineering and Public Works Department for 16 years until he was fired after his fourth DUI. He said he has lived on the streets for 11 years.

He walks 4 miles to the Immunotek Bio Center at Lake Worth Road and Military Trail where he gets $80 for selling his plasma twice a week.

Joe Miller, 48, said he was kicked out of the house by his step-mom after his father passed away. He said he works as a construction laborer.

“Believe me, I ain’t here by choice,” said Miller, who hopes to save enough money to get an apartment.

One man, who asked that his name not be published, is a licensed tile worker with a slick website. “I don’t want my customers knowing I live like this,” he said. “I just need to save up so I can get out of here.”

Erica Edler, 51, arrived two weeks ago after getting kicked out of her daughter’s efficiency. “Her old man doesn’t want me there,” she said. “And he’s paying the bills.”

Her daughter went to Walmart, bought a tent, sleeping bag, air mattress and a cooler and moved her mother to Tent City.

“I even have a portable stove. No one has stolen it yet,” said Edler, who gets daily visits from her 7-year-old grandson.

An American flag hangs over the entrance to the tent occupied by unemployed electrician Mike Bartholomei, a reminder of his service in the Navy. He said he once attended Palm Beach State College, across the street from the tent camp. Now he returns to the school to use the restrooms and power his smartphone.

Electrical outlets also can be found at other park pavilions. There’s a solar-powered electrical outlet inside Tent City, but vandals destroyed it a few weeks ago.

“You’ll never go hungry out here,” Bartholomei said.

People from nearly a dozen church groups and charities, each with county permits, come by just about every day with lunches and hot dinners. Once in a while, strangers drop off boxes of pizza.

Two portable toilets have been posted next to the restroom building, which used to be open 24 hours a day. Now, it is locked from 11 p.m to 6 a.m. after homeless people were caught using the building as a shelter.

Volunteers with Rebel Recovery stop by every day handing out kits of Narcan spray, which combats overdoses. Visitors from churches offer prayers and counseling.

On Jan. 25, county social workers showed up for the annual Point in Time count of the county’s homeless population. They arrived at sunrise in hopes of catching Tent City residents who have jobs before they leave for work.

“During the day you can go into Tent City and hardly anyone is there. Why? Because they’re working or out looking for work,” said Francky Paul-Pierre, who started a charity called A Different Shade of Love.

Paul-Pierre’s charity provides sleeping bags and toiletries for Tent City residents — much to the dismay of critics who say charities are only helping to enable the tent encampment.

“I get a lot of backlash,” Paul-Pierre said. “But if I was out there, I would want someone to give me some deodorant or say hello to me or give me a bus pass.”

But county parks staff said so many items are being dropped off at Tent City that they often wind up in trash cans. The county prefers that good Samaritans donate Tent City items to permitted faith-based groups or to homeless-advocacy groups such as The Lord’s Place and the Salvation Army.

The couple dozen Tent City residents interviewed in January by The Post said they understand why park users and residents might be afraid of them. But they claimed most of the troublemakers who generate complaints from park-goers don’t live in tent city.

“Don’t judge us. We’re not all bad. Everybody falls on hard times,” Edler said. “Come on by and visit me. I’ll give you a tour.”

Many tents look brand new because they are — bought off store shelves and donated by church groups and good Samaritans.

Inside the tents are blankets, mattresses, hot plates, grills.

Rodriguez’s tent has a small bookshelf stocked with a dozen titles including a Queen Elizabeth biography, a history of European Jews, the Janet Fitch novel “White Oleander” and his latest find — “The Unofficial Guide to Starting a Business Online.”

Residents tend to hang out in clusters, looking out for one another.

“I’m going to make some coffee. You want some?” Casal called out to Rodriguez one morning. “I’ve got a grill.”

Rodriguez hesitated. “If I’m going to light up a charcoal grill, I want to have steak. I don’t want coffee,” he said.

Freddy Negron, a 59-year-old Army veteran, said he purposely set up his tent at the west end of Tent City to be away from tent-dwellers he considers troublemakers.

“I don’t want to be here, but I’ve got nowhere else to go,” Negron said two weeks ago.

A few days later, a representative with Stand Down House, a veterans support group, picked up Negron and put him in a hotel.

Hill and Irwin also managed to escape from Tent City late last month, if only for a short while.

After feeling contractions Jan. 20, Hill got a ride from a charity worker to St. Mary’s Medical Center in West Palm Beach. Irwin was grateful that he was allowed to stay in her room, sleeping on a chair and sharing her hospital food.

On Jan. 25, she gave birth to a girl, Lucy-Sue, named after Hill’s grandmother.

The next day, Hill said, she got a visit from a social worker for the state Department of Children and Families, who informed her that Lucy-Sue would go into foster care or be put up for adoption when the infant, born prematurely, was well enough to leave the hospital.

Hill said she understood: “I can’t take that baby to Tent City.”

Five days after giving birth, Hill kissed her child goodbye and started making her way back to John Prince Park.

Staff researcher Melanie Mena contributed to this story.

https://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/20200204/tent-city-for-homeless-rises-in-john-prince-park